The Wildlife Guide Book for South India - How it Happened

- Surya Ramachandran

- Jul 6, 2022

- 8 min read

The year was 2012. David Raju and I were naturalist guides working at Forsyth Lodge in Satpura Tiger Reserve. In those days, Satpura was a park where seeing a big cat was a rare event, a place that broke most of the stereotypes of Central Indian parks. The key players in our safaris, wilderness walks and canoe expeditions were the lesser fauna, pretty much everything we came across on our excursions from birds to insects to geckos and frogs. The area did boast high numbers of sloth bears, an animal we all fell in love with owing to the amount of time we spent with some of the bold individuals. Our heavy backpacks were filled with field guides, on mammals, birds, dragonflies, butterflies, reptiles etc. We had to depend on the knowledge of things less sought after, the stories less often told, to make our excursions exciting. The field guide books played a vital role in helping us with this task, and the heavy load did help us shed some weight. Thanks to working in this park, our outlook towards a wilderness and how we approached it changed drastically, even when we visited other popular tiger reserves like Ranthambore, Kanha and Bandhavgarh. Places like the grasslands of Kuno, the flatlands of Bundelkand, sal woodlands of Panchmarhi and the eastern Maikal forests of Amarkantak excited us as much or even more than seeing a big cat strolling towards us down a forest path. Over time we had built up a comprehensive repository of information to the area we consider Central India, across all seasons, habitats and micro-habitats.

An idea of a book born out of a gift from South Africa

In 2013, a naturalist friend of us gifted us with a book. A photographic guide book on the wildlife of Southern Africa by Duncan Butchart. It was a beautiful piece of work with simple information, perfect pictures and put together in a seamless design that made the idea of biodiversity less daunting and even more welcoming. Something that we as guides try to achieve on a daily basis. A book like this was missing in the Indian context.

As soon as we saw this, David and I decided to start work on putting together something like this for our region, Central India. On one cloudy monsoon morning in Satpura, we sat together with a varied list of publications both old and recent, and started adding information into a word document. We had no idea how to put together a book or where to start. But we kept writing, and eventually thanks to the help of experienced friends like Pradip Krishen and Sheema Mookherjee, we published our first book in 2015, the Photographic Field Guide - Wildlife of Central India. The book was circulated to all the park guides and guests who visited the landscape and we could see the difference it brought about in guiding, information exchange and overall curiosity levels, both for the guests and even the guides.

Monsoon sojourns in the Western Ghats

The season in Central India lasted from October to June after which the parks shut for the season of rain. This was the time we had to explore other parts of the country. Being residents of South India, we naturally spent a lot of this time in the Western Ghats and the eastern coastal scrublands. David’s interests in frogs and dragonflies, and his association with many of the research groups that were working in Kerala kept us constantly updated on the data on these groups, the taxonomic updates, ecology etc. Every walk in this area added a ton of information to our knowledge banks thanks to the various experts we accompanied, sometimes as photographers and sometimes as field hands.

Our natural curiosity developed over the years in Satpura kept us constantly looking for questions and trying to seek answers, from reading publications to nagging everyone from friends, photographers, citizen scientists and researchers.

A landscape with plenty to offer

Over the years we had covered a huge part of the Western Ghats and parts of the Eastern Ghats, with information and photographs of everything from the critically endangered Resplendent Bush Frog Raorchestes resplendens of the high Anamalais, the Kudremukh Shieldtail Pseudoplectrurus kudremukhensis occurring in the high sholas near Kudremukh peak, the breeding colours of the White-winged Tern that stopped over in Pulicat and Kundapura, to the Myristica Sapphire, a beautiful damselfly endemic to the foothill Myristica swamps of southern Western Ghats.

South India was not just the land of such beautiful jewels but was more of a conglomerate of various habitat mosaics that, when coupled with the geology of the area, led to a unique and diverse species group that is best experienced on foot. The joy of exploring the wilderness on foot is lost in most of popular parks but was still relevant in many ways in South India. Walks, not just in the pristine sholas or grasslands, but even in plantations of tea and coffee, rice paddies, urban wetlands, beaches, dry hillocks in the Deccan to exploring one’s own garden, brought out the essence of South India. We had done these walks many times with researchers and experts who introduced us to a world that most of us may ignore. We decided to try and attempt a book that helped us share our joy of exploration with everyone and made it easier to decode and appreciate the wilderness of Peninsular India.

Attempting a book on South India

With the information collected over all our explorations, the confidence provided by the backing of expert researchers of each taxa and the data logged by citizen science and enthusiasts over the years, we dared to attempt a comprehensive field guide to the mammals, birds, butterflies, dragonflies, reptiles and amphibians of South India. There were four major challenges here.

The first was the enormity of species that occurred here as compared to Central India. In our earlier book we featured 20 amphibians of Central India but here we faced around 240. The story was similar for all six taxa. The heterogeneity of habitat was another complex matter unlike the comparatively smooth mosaic of the Central Indian landscape.

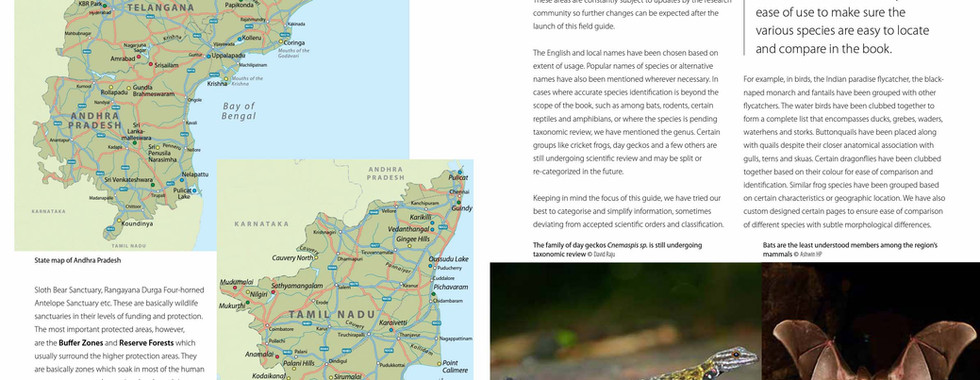

The second major challenge, which was more of a realization, was that South India was much more than just the Western Ghats. There was a disturbing lack of knowledge of the biodiversity of the Deccan plateau, south-eastern plains of Tamil Nadu and the northern Eastern Ghats. We had failed to realise the enormity of the species diversity and even the endemism that these landscapes support. For example, north Godavari areas like Maredumilli, Papikondalu and Araku valley supported a huge range of species that were better known from north-eastern India, a wide range of endemic reptiles apart from a splash of Western Ghats and Deccan plateau species. Understanding this diversity, distributions, visiting such landscapes and gathering the right information for all these places was something we did, after we started to write the book.

The third challenge was, creating a book with such large species diversity, 1920 species, within the realms of what we call as field guide books. It needed to be compact and light, yet comprehensive and with good size images and relevant text. Our experience of writing the Central India book and more importantly, our editor Faiza Mookerjee and our designer Mugdha Sethi, were instrumental in helping us make a guide book out of our large manuscript.

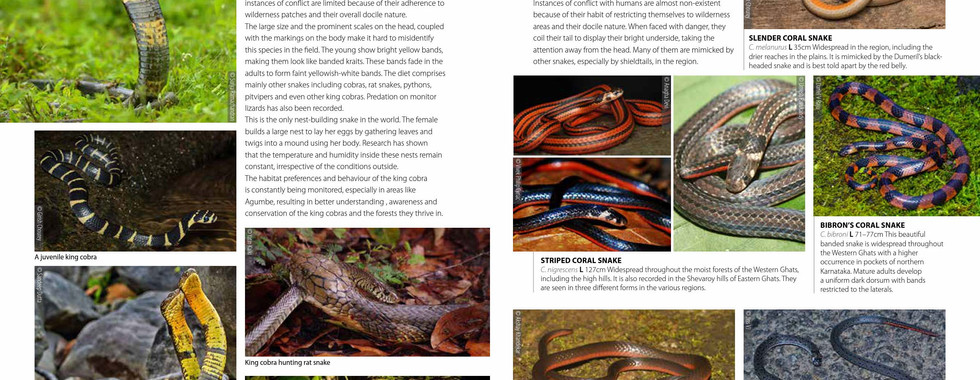

The last hurdle was more about the taxonomic arrangement of species and groups with complex identification keys. Despite the fact that we often came across Caecilians in our field visits, we never bothered identifying them because of a mix of laziness on our part and the complexity involved. We literally had to learn about these species, key out our images and lay out the pages on these limbless amphibians in as simple a way as possible. Identification of species groups like Indirana sp. frogs, Hemidactylus sp. and Cnemaspis sp. geckos and even some warblers were beyond the scope of the book in terms of the language we used in lieu of keeping it simple and the limitations brought about by a photographic guide book. We could not use terms like pre-cloacal femoral pores or talk about lengths of digits in frogs when we talk about species identification. This was a major challenge and something we think we addressed using a mixture of disclaimers, in-depth introductions to such complex groups and most importantly, splitting them based on distribution and visible external characters to at least help the enthusiast indicate and narrow down species.

Sleepless Nights, Many Learnings and an exciting Rediscovery in plain sight

In the course of putting together our book, two things happened constantly, a search for good images and interactions with various experts. We had to go through multiple image repositories and banks that were available online and in papers to find one image that depicts the species in its rightful form. Sometimes there were described species with no images, just old illustrations or museum specimens. There was so much that we learnt during these searches and conversations. Going through leaves of the various Fauna of British India series, we learnt about many such species which were considered to be lost over time. Macromia sp. dragonflies and Shieldtail snakes were two such groups. Finding images of these species involved looking for misidentifications in existing image banks and fresh searches for those species. It can be quite surprising where such species turned up eventually.

One such mystery element was the Golden Shieldtail Plectrurus aureus described by Beddome in the late 18th century using a specimen collected from a particular hill in Wayanad. Subsequent recent surveys in that area didn’t help in finding this species. We had almost given up hope and added that to the list of species which we mention in text without a supporting image until the message from our dear friend from the Nilgiris, Rohan Mathias. His friend’s 8 year old son Dhruva Gowda, came across this snake while digging up his garden. They sent photos to Rohan which eventually made its way to us. At first sight we were sure that we had struck gold. A visit by our friend and an expert on the group, Vivek Philip Cyriac, helped us confirm the species. A rediscovery after 140 years in plain sight thanks to a possible type locality error, an inquisitive kid, two desperate authors and the knowledge of an expert.

Finishing The Book

After two years of wrestling with the volume of information and new species additions, we finally went for print in Hyderabad at Pragati Offset. Even then we took the opportunity provided by a Sunday to visit Srisailam, a place we had written about but never visited. We wanted to see the Telangana plateau endemic, Nagarjunasagar skink Eutropis nagarjunensis, a stunning rock dwelling skink which we wanted to see ever since the day we got our first image from researcher Chethan Kumar. Thanks to him accompanying us, we saw many individuals along with reptiles and birds that lived their lives in the granite hillocks that rose above the Telangana plateau.

The excitement we felt on seeing the first picture and writing about this skink in our own book and later managing to find it in its habitat- is exactly what we wish to transfer, both as naturalist guides and authors, to everyone who travels with us or reads our books. South India has a lot to offer in every corner for those who are aware of its diversity. We have had an incredible journey putting this book together and we wish it starts a new journey of curiosity, awareness, conservation and conscious travel for everyone who travels with our book.

Comments